What is joint hypermobility?

Joint hypermobility simply means that you can move some or all of your joints more than most people can. You may have been aware from an early age that your joints were suppler than other people's. You may think of it as being double-jointed. If a number of joints are affected your doctor may refer to this as generalised joint hypermobility.

Hypermobility itself isn't a medical condition and many people don't realise they are hypermobile if it doesn't cause any problems. It might even be an advantage in sports, playing musical instruments or dance.

However, some people with hypermobile joints may have symptoms such as joint or muscle pain and may find that their joints are prone to injury or even dislocation. If you do have symptoms then you may have joint hypermobility syndrome – also referred to as benign joint hypermobility syndrome (BJHS) or sometimes Ehlers–Danlos syndrome type 3. It may be useful to think of it like this:

Who gets joint hypermobility?

Some people are more likely than others to have hypermobile joints. The main factors that play a part are:

Genetics

Hypermobility resulting from abnormal collagen or from shallow joint sockets is likely to be inherited. However, we don't yet know whether joint pain linked to hypermobility might be inherited.

Gender

Women are more likely than men to have hypermobile joints.

Age

The collagen fibres in your ligaments tend to bind together more as you get older, which is one reason why many of us become stiffer with age. Hypermobile people who are very flexible and pain-free when younger may find that they’re less flexible when they reach their 30s or 40s and that stretching movements more uncomfortable.

Training/exercises

Joint hypermobility can sometimes be developed, for example by gymnasts and athletes, through the training exercises they do. Yoga can also make the joints suppler by stretching the muscles.

Other conditions

Many people with Down’s syndrome are hypermobile. And hypermobility is also a feature of some rarer inherited conditions including osteogenesis imperfect, Marfan syndrome and some types of Ehlers–Danlos syndrome.

Symptoms

Although hypermobility itself isn't a medical condition, some people with hypermobile joints may be more likely to have aches and pains when doing everyday tasks. Symptoms of joint hypermobility syndrome include:

Causes

Four factors may affect whether or not you have hypermobile joints:

Diagnosis

Your GP will be able to make a diagnosis of generalised joint hypermobility or joint hypermobility syndrome by examining you and asking you a series of questions.

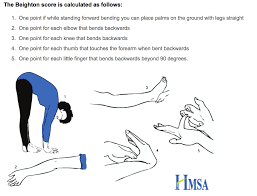

The Beighton score is a quick measure of your flexibility using a standard set of movements at the thumb/wrist, fifth finger, elbows, lower back, and knees. A high Beighton score means you’re hypermobile but doesn’t mean you have joint hypermobility syndrome. If you have problems with joints other than those included in the Beighton score, then you should mention these to your doctor. Other joints which may be affected include the jaw, neck, shoulders, mid-spine, hips, ankles and feet.

The Brighton criteria take into account how many hypermobile joints you have and whether you've had pain in those joints. If you have four or more hypermobile joints and have had pain in those joints for three months or more then it's likely that you have joint hypermobility syndrome. These criteria also take account of other concerns such as dislocations, injuries to the tissues around the joints, and lax skin.

Treatment

Joint hypermobility itself isn't something that can be 'cured' or changed. It's just the way your body is built. However, where it causes symptoms, these can often be controlled by pacing your activity. However, drug treatments are also available if you need them.

Physical therapies

Research has shown the value of exercise. In most cases you can ease your symptoms by doing gentle exercises to strengthen and condition the muscles around the hypermobile joints. The important thing is to do these strengthening exercises often and regularly but not to overdo them. Use only small weights, if any.

You can use splints, taping or firm elastic bandages if you need to protect against dislocation. An occupational therapist or physiotherapist can advise on these.

Managing your symptoms

There are several steps you can take to help yourself in your daily life.

Regular exercise is important as part of a healthy lifestyle, and there’s no reason why people with hypermobile joints shouldn’t exercise. However, if you find that certain sports or exercises involve movements that cause pain then you should stop these activities until it's clear why there is pain. With the right strengthening exercises it may be possible to return to these activities without increasing pain. A physiotherapist can advise you about exercises to improve control of the movements and loads required in your preferred sport or exercise.

Swimming can help, where the weight of your body is supported by water, although breaststroke can irritate the knee and hip, so it's best to paddle your legs. We also recommend cycling.

If any of your joints dislocate regularly it may help to wear a splint or elastic bandage while exercising. You may need to see a physiotherapist or orthotist for supports if this is a significant problem.

Footwear

There’s a wide variation in the shape of the foot in people who are hypermobile. Most tend to have flat feet but a few have a high-arched foot. Special insoles in your shoes (orthoses) may help to support the arch of the foot. By re-aligning the foot and the way the body's weight passes through the legs it may help balance and reduce pain in the foot, ankle, leg, hip and lower back.